Raj, as our chef de cuisine whenever we hosted the discussions over at Tanjong Pagar, served up food inspired by the book – crepes with duck & fig and ham & cheese fillings, and duck and chicken & prawns spring rolls. Merci, Raj, comme toujours.

Aaron moderated the discussion; Amit and Luke were there to show their support.

What did we like about the book? Food and France, according to Raj, were the two factors that he approved of. Miss Toklas was also a contributing factor, whom Raj said reminded him of his lesbian friends. Overall, he thought the book felt “real” and was a nice read. Har enjoyed the way that the book was written; he appreciated its specificity and how accessible the text was. Aaron agreed, saying that the writing was beautiful and cited the first chapter as “amazing”. Timmy commended Truong for the thorough research she conducted for her first book.

We questioned the meaning of the book’s title. Raj talked about the usage of salt in French cuisine, and briefly explained that for one to become the top chef in France, he has to master its cuisine. Timmy brought up the quote about salt existing in the kitchen, sweat, tears, and the sea, and viewed it as the ingredient that gives any dish its flavour. He alluded that life is not always sweet; there is always a little salt to give it more taste and flavour. Aaron opined that it is about ambition.

In Chapter 19, Miss Toklas instructed Binh not to use salt in his cooking. (“Salt is not essential here.”) What we have derived from that exchange was a showcase of who the superior in the house was (Raj); an indication of the characters, highlighting the charmed life Alice has been leading (Aaron); a no-salt diet requirement (Timmy). “Because it may lead to high blood pressure,” Raj quipped with regards to Timmy’s observation.

We also talked about the significance of food in the book. Aaron thought the ways in which food was described was very sensuous, to which Raj explained that food was used as a form of seduction. “Trust me, I know it!” he boldly proclaimed. Har then brought up the plentiful mentions of rice within the book and what it meant. Raj quipped that it showcased how versatile Asians can be, i.e. being able to adapt to different kinds of situations as well as the varied tastes in men we have.

If food is the metaphor for sex, then what is love? Raj brought up the bit about quinces. (“To answer your question, Gertrude Stein, love is not a bowl of quinces yellowing in a blue and white china bowl, seen but untouched.”) According to him, humans and quinces are not dissimilar – “People have to be given the right amount of heat, to be cooked and simmered (like quinces) before they attain the ability to love.”

Binh, the protagonist of the book, was brought up, which led to a discussion on his name, and why there were instances of characters not using their real names when introducing themselves. Raj vehemently said Binh was not his real name. “We don’t even know his real name!” Aaron said, before proclaiming that names are important in that it gives one his identity. Timmy thought that Binh giving false names during encounters with other people was his way of creating a new identity for himself. Aaron added that Timmy’s explanation was akin to an outsider looking in, before further questioning Truong’s intention of creating him as a gay character on top of being a second-class citizen in a foreign country.

The pronunciation of Binh’s name was also briefly touched on, with Har asking whether this was racist as none of the Caucasian characters could even pronounce his name correctly. Aaron and Raj both agreed that “Ang Mohs don’t care”, further perpetuating the notion that they really are racist.

An example of Binh’s name being “mangled” is when Sweet Sunday Man started calling him Bee. Timmy felt that that was used as a term of endearment, while Aaron equated it to Binh being a “honey bee”. Raj then explained how Caucasians tend to call others by the first initial of their names, i.e. A for Aaron, T for Timmy, and so forth. Very Gossip Girl.

Despite his affections, Sweet Sunday Man still made Binh steal The Book of Salt. Gertrude Stein wrote about Binh in the book, which caused Aaron to question whether anyone – even the great Gertrude Stein – could describe him perfectly. The part in which Sweet Sunday Man said that Stein captured Binh’s essence perfectly only caused Raj to exclaim that “Americans tend to agree with their countrymen.” We all agreed that Binh did not particularly reveal his true self throughout the book.

Varying opinions were shared when we talked about Sweet Sunday Man. Was he in love with Binh? Was he purely using him for sex? Was Sweet Sunday Man vindictive, since he used Binh to steal the book? Aaron asked whether he was a bad guy through and through. Raj said the only reason why Sweet Sunday Man was called as such was because it came from Binh’s point of view.

Is this book homophobic? Aaron finally tossed out (one of) his favourite question(s). Raj said the book made it look like homosexuals cannot find love. Aaron also added that the book depicted homosexuals as evil; Binh was a stereotypical gay man; lesbians were painted as selfish bitches.

Aaron read out loud the last passage of the book, and asked everyone what it meant. Timmy correctly guessed that it was about suicide. We briefly discussed about the “you” mentioned in that bit, which could have been referring to his mother, or his grandmother. It could even be about love or just holistically used as a metaphor.

Speaking of suicide, we moved on to why Binh kept hearing the Old Man’s voice in his head. The best quote used to describe the father: “He is a bloody cibai!” (© Raj 2013). Har viewed it as Binh’s criticism of himself, while Raj felt that it was his way of fulfilling his father’s expectations of him. Timmy thought he was delusional, and then brought up the scene of him burying his father alive.

Binh’s paternity was also questioned, with Timmy believing that The Old Man was not his biological father due to his mother’s affair with the schoolteacher. Aaron, however, didn’t think it was plausible and instead, suggested that Binh may have made the story up.

Aaron noted that religion played a big theme within the book, though Raj was unsure whether the author was against it.

When it came to favourite characters, Har picked Minh (up until Chapter 8, anyway) as he found the sous chef cool and was often dishing out advice to his younger brother. Both Timmy and Raj selected the mother, who, according to T, was “the Destiny’s Child of Vietnam in the 1920s”, while Raj likened her to The Little Nyonya, who was always busy in the kitchen, has got the guts to go to a different church from her husband’s, and was accepting of Binh. In terms of least favourite characters, Timmy disliked the (ex-) Madame’s secretary, calling her a slut and a bitch. Raj chose Sweet Sunday Man, saying that he was manipulative and had the nerve to break it off with Binh on a Post-It note. He then cited Carrie Bradshaw’s cardinal rule on breaking up with anyone using a Post-It note. Aaron found the grandmother to be selfish as she sold her daughter off to be matchmade before killing herself, just so that she could join her deceased husband in the afterlife.

We rounded up the session by asking one another what we don’t like about the book. Raj thought that it was full of stereotypes, though overall, he does not and could not hate the book. Har found the food references too tough to follow, and after the discussion, thought the ending was horrible. Timmy, who by then could not hold back his vitriol, said he found the book boring and monotonous, joking that he would rather watch paint dry or grass grow than read it. He didn’t think there was any satisfaction from reading the book, and could not appreciate Truong’s writing style. Aaron thought the same. “The writing is so beautiful, yet it’s a beautiful nothing,” he poetically said.

A cozy, intimate discussion between Timmy and Aaron, like when the book club first started.

A cozy, intimate discussion between Timmy and Aaron, like when the book club first started.

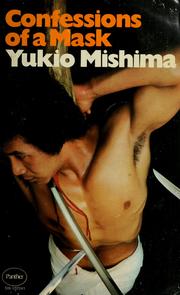

The biggest complain we had about the book was the way it was written: Dominic felt it was unlike the “Japanese style of writing”, comparing Mishima to Murakami. Raj thought the book was draggy, describing “mundane things in mundane ways.” Alexius did not like the ending and was left disappointed by the book. Timmy found it uninteresting as a whole.

The biggest complain we had about the book was the way it was written: Dominic felt it was unlike the “Japanese style of writing”, comparing Mishima to Murakami. Raj thought the book was draggy, describing “mundane things in mundane ways.” Alexius did not like the ending and was left disappointed by the book. Timmy found it uninteresting as a whole. From St. Joan to St. Sebastian

From St. Joan to St. Sebastian

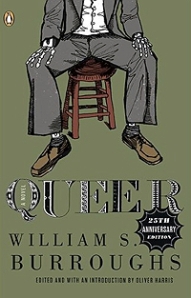

We started with Queer, and talked about how the introduction affected our reading (the murder of his second wife, and writing as inoculation).

We started with Queer, and talked about how the introduction affected our reading (the murder of his second wife, and writing as inoculation).

A great attendance: Suffian, Timmy, Har, Sam, Lydia, Gabriel and Aaron.

A great attendance: Suffian, Timmy, Har, Sam, Lydia, Gabriel and Aaron.

Doyler’s rape was brought up as well as what happened that made MacMurrough feel that he was not in control. Timmy quipped that it was because D was a power bottom, while Jiaqi opined that M needed D more than vice-versa.

Doyler’s rape was brought up as well as what happened that made MacMurrough feel that he was not in control. Timmy quipped that it was because D was a power bottom, while Jiaqi opined that M needed D more than vice-versa. In rounding up the discussion, we went around asking for something positive of the book. Raj promised to finish reading it, even though the pdf version gave him headaches. Amit thought it was romantic of the author to continue working on the book to 600+ pages, as opposed to taking the quick way out and cut it short. Jiaqi thought it was a good book and themes were very well done. Har, probably the only fanboy of the book, said that it was touching and “made him cry a lot.” He also commented that the writing technique was “very Irish and filled with proses.”

In rounding up the discussion, we went around asking for something positive of the book. Raj promised to finish reading it, even though the pdf version gave him headaches. Amit thought it was romantic of the author to continue working on the book to 600+ pages, as opposed to taking the quick way out and cut it short. Jiaqi thought it was a good book and themes were very well done. Har, probably the only fanboy of the book, said that it was touching and “made him cry a lot.” He also commented that the writing technique was “very Irish and filled with proses.”